| Reports of visits to Japan of POWs |

Friendship meeting with Japanese citizens in Tokyo

October 16, 2013

| Mrs. Marjean McGrew | Mrs. Esther Jennings | Mrs. Lora Cummins |

| Q&A | Closing remarks |

|

Date: Wednesday, October 16th, 2013 14:00-16:30

Place: Tokyo Azadudai Seminar House in Tokyo

Organizer: Japanese Society for Friendship with ex-POWs and Families

Cooperated by: POW Research Network Japan (POWRNJ); US-Japan Dialogue on POWs

Chairs: Mayumi Komiya; Yoshiko Tamura

Interpreter: Makiko Kamiyama

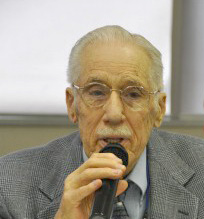

Mr. Marvin Roslansky (91) |

|

He became a POW on Guam Island.

He was transferred to Japan on Argentina Maru and was interned in Zentsuji Camp in Kagawa Prefecture in January where he was liberated.

*Please see the memo about Zentsuji Camp >>PDF

I went to Lakeville High school and graduated in 1940. In 1940 in the US … and England and Germany were already at war, so I decided joined the service. I joined the Marine Corps in March 1941 and took my training in San Diego. I went to San Francisco to work for a short while and then shipped to Guam in September 1941.

In Guam it was run by the navy so we had a 147 Marines out there with a couple of hundred sailors because Guam was the hospital for … In December 7th after the war started the Japanese started to bomb us and on the 10th of December, 1941 the Japanese invaded Guam.

We were taken prisoner on Guam and sent to Japan in January, 1942. We went to Takamatsu and I spent all my time in Takamatsu working on holding docks.

We stayed in Japan until September 15, 1945 when I returned back to … duty again. I spent most of my time after … dismantling automobiles.

During the time in Takamatsu (Zentsuji Camp) we worked on loading docks, unloading freight from the railroad cars, back into the warehouses, back and forth. We spent 12 hours a day in a two-week period all through war. After the atomic bomb was dropped we were told that we did not have to work anymore.

Mr. Erwin Johnson (92) |

|

He became a POW in the Philippines and experienced"Bataan Death March".

He was transferred to Pusan (Korea) on Tottori Maru in October 1942 and sent to Mukden Camp in Manchuria where he was liberated.

I was 19 when I joined the Army Air Corp in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1940. I was sent to Savanna, Georgia and there I helped load a troop train and we headed out to San Francisco. From San Francisco we boarded the SS President Coolidge. It was a cruise ship, but turned into a troop ship. We left there November 1, 1941 and arrived in Manila on November 20th, 1941. And I was sent to be put on a boat, cross Manila Bay and went over to Bataan, to the southern tip of Bataan, called Mariveles.

On Bataan we found a delayed action against the Japanese and, of course, General MacArthur kept telling us that there is a convoy on the way and that convoy never did show up. So, we were surrendered on Bataan by General King. We went back to Mariveles and the Japanese rounded us up and put us in groups of about 150 men and we began the famous Bataan Death March. And that is the time that I lost my freedom. It is a terrible thing to lose your freedom.

On the Death March we walked 65 miles in six days. We were fed one cup of rice and we had water - (only) what was in our canteens. We went up to Camp O`Donnell and I stayed in a few camps, different camps, in the Philippines around Manila. And then we were put on a Japanese hellship, which we called them, the Tottori Maru. And we went up to Formosa and we stayed there awhile. Then we started north again and an American submarine shot two torpedoes at us, but the captain maneuvered his boat and

We landed in Pusan, Korea and they put on a train and took us up to Mukden, Manchuria. Now most of the fellows here have been camps in and around Tokyo, but I was in a camp in Manchuria. I stayed there until August, 1945. Then we were sent down to the Port of Dalian, put on a navy ship and I felt that I had regained my freedom when I saw the Stars and Stripes on the ship. Thank you.

Mr. Robert Heer (92) |

|

He became a POW on Mindanao Island, ThePhilippins.

He was sent to Taiwan on Lima Maru and interned in Karenko Camp in September 1942, then to Heito Camp and No.6 Branch Camp in Taipei.

He was transferred to Japan on Taiko Maru and interned in Kameda Camp (Hakodate 2-D, Hokkaido) in February 1945.

He was moved to Akabira Camp in May 1945 where he was liberated.

*Please see the memo about Kameda Camp >>PDF

*Please see the memo about Akabira Camp >>PDF

My name is Robert B. Heer. If any of you have computers, write my name – Robert B Heer - down on your computer and you will find 3 or 4 stories that I have written and put online. One thing that I want to mention today is that I graduated from high school in Riverside, California in 1940. A week later I was in the Air Force. When I was going to high school.

I would like to mention that one of my companions in high school when I was the Reserve Officer`s Training Corp was a Japanese boy by the name of Harold Shirataka Harada. He and I were both buddies along with four other guys we used to chum with and the ironic thing about our lives was that Harold was sent to a relocation camp in Poston, Arizona, then later transferred to camp in Topaz in Utah. Later on he was located to another camp in March 1942. Two weeks later I was captured by the Japanese. We both become prisoners of war in a way during that particular month. My wife and I met Harold afterwards at a class reunion, but you might be able to find a lot of information about the Harada family in Riverside, California. They have a national museum there. Thank you.

The only thing that I was to say is about the typical POW life was not unpleasant because we did not understand at that time the Bushido samurai philosophy of the Japanese soldier prior to World War II and during World War II, but we learned to read their expressions and their movements and their attitude, and from this we would judge if we were in a place to talk with them or not talk to them. And with that I will close. Thank you.

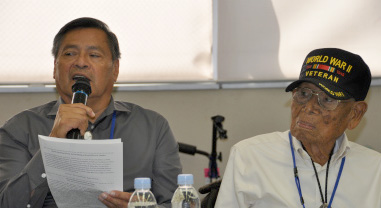

Mr. Phillip Coon (94) |

|

He became a POW in the Philippines and experienced "Bataan Death March".

He was transferred to Taiwan on Hokusen Maru and was interned in Inrin Camp in October 1944.

He was transferred to Japan on Melbourne Maru and was interned in Kosaka Camp, Akita Prefecture in January 1945 where he was liberated.

*Please see the memo about Kosaka Camp >>PDF

My name is Micheal Coon and he has asked me to speak on his behalf. Mr. Philip Coon was born in … Oklahoma on May 28, 1919. He is a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation tribe in Oklahoma. Our chief calls him our national treasure of our tribe. He is 94 years old. There is a ceremonial ground in our Indian culture is the alligator clan. This ceremonial ground is called New Yaka. That is our culture, we have our ceremonial dances and stuff that we perform through our tribe and stuff. We have 27 different counties and stuff. Each member has their own clan. And so each clan has their own tribal grounds. He graduated from high school institute in 1941. He enlisted in September 1941 and was assigned to the 31st Infantry H Company as a 30-caliber machine gunner. … 1919.

And (he) was captured in Manila in 1942. Having being forced to endure the Bataan Death March he was transported to Camp O`Donnell where he was placed on burial detail for two years. He was then transported to Taiwan on October, 1944, then to Sendai, Japan by Melbourne Maru on September, 1944. He was then placed at Kosaka, Akita where he worked there as slave labour in the copper mines until his release from prison He was liberated from the prison camp just after they dropped the bomb, they were freed.

He has been back to the Philippines where he was captured and also coming here to Japan more or less closes a chapter on his military experiences and stuff. He has always told us. His favorite saying that he tells us is, "Love thy neighbor as thyself." So within him, he has found peace with the Japanese. He still has not forgot his comrades though who were lost at sea, on the battlefield, camps, and many that he had to bury. But as he said that is all behind him. He has gone forward with his life. He is a Deacon at a Baptist Church in Oklahoma. He is a member of the Southern Baptist.

In our language, and I know that in your language you have a saying for Thank you. In ours, we say Mado. Thank you.

Mrs. Marjean McGrew (86) |

|

Her late husband was Mr. Alfred McGrew.

He became a POW on Corregidor Island, the Philippines.

He was transferred to Japan on Noto Maru and was interned in August 1944.

He was interned some camps such as Omori Camp in Tokyo, Tokyo 24-D in Kawasaki and Suwa Camp in Nagano Prefecture where he was liberated.

*Please see the memo about Suwa Camp >>PDF

I'm Mrs. McGrew and my husband was Alfred and he was taken prisoner on Corrigedor Island and he went through several camps, but the worst one that he was in was for two years building an airstrip in Manila with pick and shovel for the Japanese, which they never got to use. Then he was shipped up to Japan and he was in several camps up there. And the last one was Suwa.

He was in Suwa too awful long and then was released, but we traveled up there several years ago and he said that they had a loose board in the fence and they went out at night and stole potatoes from the farmer around there and then one night he and his buddy got lost and could not find their way back, and all they could do was pray until daylight and then they saw the camp light on. They made it back through the fence safely and they would hide the vegetables under their beds, their mats.

And when we traveled over there, there was an old couple came walking out to the road because there were a lot of newspaper people with us and they knew something was going on. She walked with a little wheelchair and he walked out and was very bent over from farming and we found out that he was the farmer that Al was stealing the potatoes from. And so, it was wonderful when we met them.

And then my little friend Yasuyo, our interpreter for the whole time with us, they had a town meeting that night and my husband said, "Do you want me to buy you a bag of potatoes?" and the poor, old farmer just laughed. And so, it was such a good trip that we had. It did Al good because of all of the other things that he had been through, so it was enjoyable and fun also. That`s it.

Mrs. Esther Jennings (90) |

|

Her late husband was Mr. Clinton Jennings.

He became a POW on Corregidor Island, the Philippines.

He was transferred to Japan on Nissho Maru in July 1944 and was interned in Fukuoka 23-B in Keisen.

He was moved to Fukuoka 1-B and Fukuoka 9-B in Miyata where he was liberated.

*Please see the memo about Miyata Camp (Fukuoka 9-B) >>PDF

Thank you for coming and listening. I don`t know who you are, so I hope after we time to exchange some words. My name is Esther Jennings and I am from San Francisco, California.

I am the widow of Clinton Jennings and I will start reading just a little bit. He was in a civilian conservation corps before enlisting in the US Army. He said, "We are going to go someplace, foreign and exciting", and I think that Corregidor turned out to be very exciting. He went over on the USS Republic and was stationed at Corregidor with the 59th Co-… Battalion K., which had the big search lights. And then after he was surrendered on May 6, 1942 by General Wainwright, he was sent to some of the different camps and the big one was Cabanatuan. And from there he was sent by hell ship, the Nissho Maru to Japan and the nightmarish two-week voyage to Moji, Japan.

The trip to Moji, Japan included an attack by an American submarine war pack on the unmarked transport and he was sent out to that Fukuoka 23 to slave labour in (the) coal mines, and then transferred to Fukuoka 9-B in the town of Miyata. And, he after the war weighed at 89 pounds at 6 feet 1.5 (inch), and he had beriberi, malaria, dysentery, and pellagra.

Then he stayed in the Army for twenty-five years. He had a tour in Turkey, and Korea which was after the war, and then San Francisco. I worked for the Army. He came into my office and the rest is history.

May I please thank Mrs. Sasamoto for the research that she did on Fukuoka. I have not seen this before and I don`t think that my husband ever saw before too, so thank you so much for it. I appreciate it.

Mrs. Lora Cummins (87) |

|

Her late husband was Mr. Ferron Cummins.

He became a POW in the Philippines.

He was transferred to Japan on Noto Maru in August 1944 and interned in Mukaishima Camp in Hiroshima Prefecture where he was liberate.

*Please see the memo about Mukaishima Camp >>PDF

I'm Lora Cummins and my husband was Claren Cummins. He enlisted in the Air Force – the Army Air Force. For those who didn't know that the air force was a branch of our army and was called the Army Air Force until 1947. And that year it was made into a separate division on its own. He took basic training in San Antonio and went immediately to the Philippines. Arriving in the Philippines on the 20th of November, 1941, and as you know, the war broke out, on the 7th or 8th –whichever side of the date line you were on, and so his baggage never did catch up with him. But he was interned at Cabanatuan, and his training etc helped him.

But he spent two years in the Philippines and then spent one year in Japan. And it was on Onomichi down south (Mukaishima POW Camp) and he came back. Shortly before he was liberated he weighed 98 pounds and by the time he got home he weighed 148 pounds. I would not have recognized him if we had met on the street. But he came back and he serviced for 12 years. Bought a … business, ran that and we had a very good life. That was all. That is about all I have to say.

Mrs. McGrew

May I add something. The gentleman on the end is from our famous Indian tribes in the States, and even though they speak in a little bit different language when they call their areas, their clothes and their tribes and everything, but they are very, very beloved. And they are very strong people. And my husband told me a story when he came home from prison. He said, "The Japanese began to get very smart and they could decipher language and understand what some of the ships were saying then, some of this and that" And they said, "We have the American Indians here and they all have, there is a lot of groups. Everyone has a different language of their own. And they could speak their Indian language and the Japanese would never be able ever to understand their lingo, so I think that needs to be said about those because they are special people. I wanted you all to know it.

Q&A

Q: To Mr. Roslansky – Did you see the atomic bomb cloud from Zentsuji?

A (Roslansky): No. No. Hiroshima is about 60 miles west of us so it could be that he went over Zentsuji. The wind blows from the east to the west.

*Note: The wind usually blows from the west to the east.

Q: About the atomic bomb?

A (Roslansky): We really never knew about it. As days went by and after August 14th when Japan surrendered, then we heard more about it. It was in the news. We did not know immediately.

Q: To Mr Heer – Did you participate in propaganda broadcasting?

A (Heer): I would be very happy to. The program by the United States was called "Voices in the Night" and at the camp Karenko (in Taiwan). This was shortly right after we began to be prisoners of war and were stationed at Karenko.

Our camp commander told us that on a postcard size card that we could write a message to our parents and that they would send it to them to my parents as well as the others to their parents. They said that they would broadcast them and none of us believed them because so far they had not been very cooperative with us as much as we were with them.

But anyway, the message was taken to Tokyo and when I got home in 1945 my younger sister said, "I've got something to show you." She had sixteen letters from people - radio operators - around the United States who had picked up that message. It was broadcast from Tokyo in March of 1943. About the 27th, I believe. Anyway, my mother had twenty messages her postcards with that message on there. "We have a ham radio and we picked up this message radio broadcast from the radio station in Tokyo about your son." I've prepared a book on those. I've done a lot of research to get the names of the people who wrote those and a little bit of their life wherever I could find it. And I have prepared this book and have sent to one or two of the museums in the local area and also to the American Defenders of Corrigedor Organization for their historical purposes, but the messages came through.

Basically the message said this, "I am in fine health. I am not sick. I am working. I wish you would send me candies, cigarettes etc etc. Please send my love." And I gave the names of those I wanted to send my love to. And then I closed with, "I love you. This is your son, Bob." And that was the message that got through.

And I only wish that I had the book here to display to you, but it is one that I put together. It was something that shocked me when I got home. I never believed that the Japanese would do that.

And they called it, they had a name for it too, but the primary purpose of it I think of that effort by the Japanese was to make it a propaganda broadcast, but it backfired on them. They did not want people to know that their sons, husbands or whatever or where they were in prison camp and that was a big relief to a lot of American mothers of the United States and wives as well. That is the best thing that I can recollect to tell you about this. But it really was a surprise to me.

And the Germans did the same things with their POWs. They had the Axis Sally they called her. She worked in radio stations there in Germany and sent messages too. The only person who called me on the phone two years ago to tell me about the messages (asked), Did I have any of them in my possession? And I said that I`ve got every one of those eighteen letters that are in my possession. And she says, "I have got to tell you something. My grandfather when he died, they found seventy letters. Seventy letters" from Japan and Germany in her father`s trunk. And then she really got ambitious and decided to write a book. She has written two books so far. Her name is Lisa Spar. Lisa Spar. She recently published her book and is available.

But anyway, that is all I have to say is it that is was one of the nicest things, if that was their purpose to do that because they really relieved a lot of parents and wives that were worrying about their husbands who were in prison camps. And I thank you for listening.

Q: To Mrs. Johnson – Would you tell us about your elder brother who died in Mukden and present feelings?

A (Mrs. Johnson): Well, when my mother received the telegram that my brother had died, I was ten, I think, and I am the youngest of seven in a big family in the country. My mother had worked hard to take care of us, but that day she heard the message and she simply went into the bedroom and she just did not reappear for years in fact. She reappeared in the sense that she would come out perhaps and cook a meal sometimes or do the dishes sometimes, but basically she went into depression.

I know that now. I did not know it then. I thought she was just meditating. She read a lot, but she was not reading. So, at any rate, years went by and I went off to college and grew up and realized that she didn`t pay attention to the family. She did not have the emotional resources to do that. And at last I understood that depression is a serious thing. Today, doctors would do something about that.

But as the years have gone by I have thought a great deal about it because he was a special brother. They were all special. And over the years I have thought a lot about the situation where he died and I have been to Mukden and I saw that place. And so I could envision him struggling to get through life there, but since then I have realized that as we had a Civil war in the United States in the 1860s, and one of the Generals said, "War is hell." And indeed that is the case, war is hell. Bad things, terrible things happen wherever a person is and whether they are civilians or soldiers on either side.

Dreadful things happen, but it is over with. He is home. He is buried a small cemetery. Our town is 350 people. He is buried in that cemetery and I go often with Earl, and I go there to say hello to him and my parents. And it is in the past. It is over with. People did the best they could and life goes on.

And I have no animosity toward the Japanese people today especially the younger people. They are just little people growing up and I hope that they grow up well. I hope that ours do, too. But as I say I think the Japanese people and American people are friends today. And we will continue to work on it because friendships do require some effort. That is the way it is whether it is the person next door or the person across the continent. We need to work on it. And I am glad to have had the opportunity to do just that with this trip. It has been very important. Very important.

Q: To the widows – Have you ever heard of your husband's experience during the wartime?

A (Cummins): My husband talked the Philippines, about his experiences to me. When he first came back we started going together. He would talk to me and tell me about experiences, but he would not tell his folks. They would have liked him to start with Day 1 we did so-and-so and went to so-and-so and he just would not talk about it. And when he opened up was after he came back from a trip to the Philippines at the 25th anniversary pilgrimage to the fall of Bataan and Corregidor. He opened up and saw the situation in different circumstances. And as I told you he was over there and he … hooked up with him so he did not get to see the Philippines in normal circumstances. And he just opened up and you could not shut him up after that.

A (Jennings): So you wanted to know if they opened up to their wives after being in Japan later on. Is that correct? Did they say any new things or opened up to their husbands?

A (Woman in audience): OK, let me explain. I wanted to know as I told them that some of the wives of the POWs came to Japan like you did. They said after their husbands talked about it and they are given the opportunity to speak up whatever they think. Some of the wives said I have never heard of his experience during the wartime. His experience in Japan or Philippines whatever. So, she was very surprised and shocked to hear what had happened to him. So, the reason why those widows came to Japan with the understanding of their husband`s past experience. That is what I wanted to know.

A (Mrs. Jennings): I would like to answer that question, however, I did not know him when he came back. I did not meet him until 1960 or something and we were married in 1970. But we did go back to the Philippine islands in 1992 for the 50th, three years later, and then for the 60th we went back. And although we talked about it all the time because he gave speeches and there were a lot of things that he showed me in Corregidor. I do want to tell you one little thing. You notice how short I am. My husband was 6(feet) and 1.5(inches) and we would go on a tour some place. He was always in the back and I said I can`t see or hear (you), so come up front and sit with me. No, no you go and I will sit back here. I always attributed that to being inconspicuous when he was among the POWs.

A (Mrs. McGrew): I did not know Al long. He was a prisoner or I met him after the war. He was already home and at work in a job. The only strange things that I noticed is that he would get upset if he was watching a movie where it was wartime and the prisoners, prisons camps were on there. He would get upset when the movie was over. It was gone. He was fortunate not to have so many nightmares like many of the men did. Many of the men suffered them terrible, but I could only remember unless I did not wake up one bad one and let`s see they would not stand by a window with their back to the window. Oh no – that was a no-no because of something coming up and grabbing him or whatever.

And all the time I was married to him he never had any animosity towards the Japanese people, which I was happy for and which was very unusual because any of the men were scarce when they felt that.

So I was fortunate that way and when we went to Suwa, he was really happy to go to see that camp plus every time you see lists of the Japanese camps Suwa was never on it and to this day Suwa is not listed among the Japanese camps. And even though it was up in the boonies and it was small and it is still not listed. One of these days I am going to get angry and tell them about it and get it on the list. But he enjoyed it immensely and talked very freely with the people and with everybody.

And we were taken up there with two priests and which was just wonderful. And we were able to sleep in one of the temples, which was unusual and we happy for all of that experience.

And Dad talked about the prison camp quite frequently. One time my daughters said, "Mom, I didn`t hear Dad talking about it." I thought, "Well, I am sorry, but he spoke to me about it." He would just tell me about the hardships and things like that, and how they survived, and the food they got, which was not so good.

And to this day I have given talks because since he is gone from this earth he left all of his work and his pictures and things on cardboards and they fold up and so I take them with me and a canteen and put rice in it and put it exactly where he showed me where they had it each day and one of the helmets. And of course, when the war started all of those big guns on Corregidor were built in 1910 and 1901. I have been there. I saw them. And they were WWI guns and all of the rifles were the same thing, WWI guns. Of course, when the Japanese hit us they were so far ahead of us in everything that it was unreal. Airplanes and everything.

A (McGrew's Son): He did not speak to either one of us.

Closing remarks |

|

Thank you for coming to this meeting. Visiting Japan by flying across the Pacific Ocean must have been a psychological burden for you. Incidentally, as Mrs. Tokudome mentioned at the beginning of this meeting, among the former Allied Forces POWs, the treatment of the US POWs was a little different from that of the British, Dutch, and Australian POWs due to the relationship of the United States with Japan in those days. The reason being, by Article 16 of the San Francisco Treaty, although it was a very small amount, compensation was paid to each former POW of the allied countries. There were 203,599 of them to be exact. Since the compensation was so trifle that they complained to the court demanding more compensation from the Japanese Government. But they had a verdict went against them. With regard to the former US POWs, however, they were excluded from the compensation issue at that time.

Has the US Government ever paid compensation to you? According to the sources, the US Government was to pay the compensation to its POWs after disposing of the Japanese property and assets within the United States. For this reason, the former US POWs were excluded from the invitation program by the Japanese Government. Under such circumstances, when inviting the former POWs of the Allied countries, as a matter of course, more attention was paid to the former POWs of other than the Unites States. As from four years ago, the Japanese Government has invited the former POWs from the United States as well. We all know the US POWs made a great deal of sacrifices during their captivity. In the data relate to the Tokyo Trial, the judgment documents clearly state that the death rate of the US and British POWs was 27%. In addition, more than 600 documents were submitted as evidence by the former POWs, in which a plot on annihilation of the POWs untold today was found. We have been studying such matters existed on our side and, at the same time, enhancing friendship and deepening mutual understanding with the former POWs of the United States, the United Kingdom, Netherland, and Australia.

Just a while ago, Mrs. Johnson said, "War is hell" and brings you tragedy on which side you may be. After hearing your speeches, we will do whatever we can never to make hell once again. In other words, no more war. By learning from your experiences, we would like to enhance friendship and deepen mutual understanding with you. We really appreciate your coming all the way over from America. As is the case of the "Voice in the night", we would very much like to listen to the "Voice from America." Thank you.